I just finished reading this post on Law, Legislation and Lunacy in which my classmate David wrote:

I just finished reading this post on Law, Legislation and Lunacy in which my classmate David wrote: I’m not sure which economists David is talking about when he says “we” talk about greed? Hayek? Adam Smith? Milton Friedman? Thomas Sowell? Me? There is nothing I have learned in economics that rests on a fundamental axiom of greed. Self-interest perhaps, but greed no. They are not the same.

Deirdre McCloskey kicked off the first annual James Buchannan seminar this past Friday.

McCloskey… tackled the virtues of economics and how economists focus too much on "prudence." Prudence is a strange virtue in that it descibes a sort of patience and sound judgement, in other words things that are smart to have in them of themselves. The other virtues are good--if that's the right word--because they help others. Prudence, in its most basic form, helps the actor only.

Economists talk about prudence a lot and we have different names for it. Self interest. Risk-aversion. Rational expectations. The other thing we talk a lot about is greed, much to McCloskey's dismay.

Self-interest is the desire to better oneself and one’s living conditions. I and most others I know would view this as a good thing as long as it is not done while harming or at the expense of others. Rather than defining greed, let me turn to two online dictionaries.

Webster defines greed as:

Dictionary.com defines it as:

excessive or reprehensible acquisitiveness

I see no virtue in either of these definitions and can easily imagine that a random survey of people on the street would yield the same opinion. Very few people outside an economics department would put greed on a list of virtues. (Unfortunately, David’s point and McCloskey’s fear is that many economists would.)

An excessive desire to acquire or possess more than what one needs or deserves, especially with respect to material wealth.

This is not greed, but self-improvement. If it is desiring a better life for others, then by definition it is not greed. I must say that I don’t think I have ever heard of Greed as being holy before. I don’t think David actually means that greed is worthy of worship?

She feels greed is not a dimension of capitialism and capitalism requires all the virtues. Vices have no place in genuine free market activity. I take issue with this. Not only does greed play a fundamental (and moral) role, the flavor of greed economists talk about captures the very virtues McCloskey thinks we are ignoring.

Greed can be quite holy. Most generally it is about desiring a better life (usually for yourself, but it can also be for others).

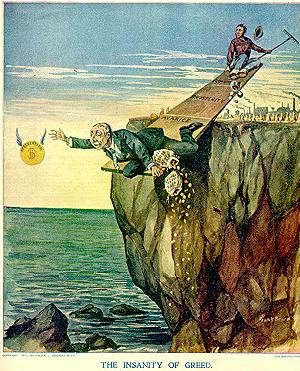

David is illustrating the very point McCloskey is trying to make – taking the rhetoric of “greed is good” to the extreme leads to the elevation of greed and money into the transcendent. Theologians would call this making a God of money. Christians would call it the worship of Mammon. Whatever way you want to call it, placing our Faith and Hope in money rather than a higher good is precisely what McCloskey (and I) fear will happen when economists focus on human beings as being mono-dimensional utility maximizing agents with no considerations beyond the betterment of their own conditions with no regard to others. Very few people I have met in life fit so narrow a description. Very few outside the economics profession view people in so narrow a way and not many economists I know do so either.

This is Hope. It also must, by definition, include the idea that people believe money (or whatever tickles their fancy) is a means to the end that is the better life. This, for a lack of a better word, is Faith. (We can expand the means framework beyond "money" to explain suicide bombers and so forth, again finding they have faith that their strategy will grant them what they hope for.)

Economists often use self-interest as a simplifying assumption and evaluate how the world would be if people tried to maximize their own “utility”. Basically saying when people are given a variety of options, they will choose what they think will bring them the highest expected satisfaction among the alternatives before them. That doesn’t sound like greed, but more like wisdom (or prudence) to me. It also doesn’t account for the whole range of human behavior.

Unfortunately, there are a number of economists who do focus on a narrow definition of self-interest which is basically synonymous with greed. Ayn Rand became very famous for holding this position. This is absolute contradiction to how the founder of economics, Adam Smith, viewed human behavior and human virtue. Smith wrote extensively on other virtues as well and viewed humanity as very multi-faceted and rich in depth. (Read “Saving Adam Smith” for more thoughts on this or, better yet, check out the “The Theory of Moral Sentiments” by Smith himself.)

I certainly agree with Smith and McCloskey on their more complex view of humanity. It would be very difficult to explain the deeper human experiences of love, sympathy, friendship, faith, respect, dignity, justice, reciprocity, etc. purely through the dimension of prudence or self-interest. It would be even more difficult to explain these through the “virtue of greed”.

David continues:

This indeed is Justice and is outside the realm of Greed. David is actually underscoring what McCloskey said – more virtues than Prudence are needed to describe the ethics that humans should follow.

We economists talk about the ethics of greed, we do not say greed is always good. We agree that taking others' stuff by force is not a moral manifestation of the so-call vice. Greed must be the motivation for trade (not theft) for it to be ethical. This is Justice.

Again, David reaches outside the scope of Prudence to describe (and support) what McCloskey was saying. Courage is a virtue and when combined with Prudence and Hope leads to risk-taking and new ventures. This is a wonderfully necessary part of entrepreneurship and needed for our economy to grow.

Greed also generates Courage, for it is what motivates people to take chances and stand up for what they believe in, and Temperance, for those that are too "couragous" don't achieve their desires.

I disagree with David, however, when he says that these virtues emanate from Greed. There is nothing magical about a lustful desire for wealth that would suddenly give an incredibly risk-averse man a spine of steel. Courage is a virtue that needs to be taught and cultivated separately from Prudence. As is Temperance (self-control). It is easy for me to imagine a greedy individual who takes great risks to gain money, only to fail and kill all of his underlings or enemies in a fit of rage. (Think about any low-budget action movie you’ve seen with a bad guy who kills all his underlings in a fit of rage after the hero thwarts his attempts at gaining wealth. I’d argue the bad guy had Greed and Courage, but no Temperance whatsoever.)

I think David makes his biggest stretch when he says:

Love is perhaps the most closely connected to Greed itself: Love for money, Love for fame, Love for others.

I’ll grant David that Greed leads to (or is) the love for money or love for fame, but how does greed lead to a love for others? Greed requires self-absorption, which is why most people disdain it.

I’ll grant David that Greed leads to (or is) the love for money or love for fame, but how does greed lead to a love for others? Greed requires self-absorption, which is why most people disdain it.David closes with this statement:

David may view Quark as a hero to emulate, but personally, I don’t agree.

It's just like Quark (from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) said. "Greed is the purest, most noble of emotions."

Not to pick on David too much, but while Quark may be his favorite Star Trek character, I was always much more taken by Seven of Nine…

11 comments:

Brian, I commend you for putting "we" in quotation marks. I believe this needs to be done much more often.

Anyway, a quote from Milton Friedman for your consideration:

"What kind of a society isn't structured on greed? The problem of social organization is how to set up an arrangement under which greed will do the least harm."

I strongly suggest the first two or three pages of "Constructivist and Ecological Rationality" by Vernon Smith, which you can find here

http://www.law.gmu.edu/currnews/smith-lecture.html

Brian, quoting the dictionary definitions are just confusing. What's "excessive?" That is, in the words of a great economist, vacuous for what's excessive to one person is sufficent for another and underpaid for a third.

Can greed be immoral? Of course it can be. Every time someone kills another for their wallet or cheats someone then it's a transfer payment--forced and unethical. But when greed motivates people to engage in mutally beneficial tranactions, then how can it be anything but moral? Society as a whole is richer, safer and happier because of greed's moral side...isn't that what virtues are supposed to accomplish?

I really do think greed has just gotten a bad rap over the centuries...so much of human activity revolved around transfer payments. Philosophers saw kings and tyrants take stuff from other people and declared "want" is bad but never stopped to ask how people fulfill that want.

jeremy h. writes: "Brian, I commend you for putting 'we' in quotation marks. I believe this needs to be done much more often."

I agree. Too often, those vague collective pronouns (is that what they're called in English class?) obfuscate things. History texts and professors have been, in my experience, the most apt to commit the "sin" of "anthropomorphizing" groups. In my opinion, a bit more so-called methodological individualism in the social sciences (including economics) and some of the humanities cannot be a bad thing.

Brian writes: "I’m not sure which economists David is talking about when he says 'we' talk about greed? Hayek? Adam Smith? Milton Friedman? Thomas Sowell? Me? There is nothing I have learned in economics that rests on a fundamental axiom of greed. Self-interest perhaps, but greed no. They are not the same."

I'd agree that economics is not necessarily predicated on greed, but only on self-interest - i.e., only that a man acts because he wishes to trade a less-satisfactory condition for a more-satisfactory one.

Reminds me of the time my anthropology professor last semester tried to tell me and the class me that neoclassical economics holds as an assumption Spencerian Social Darwinism (I think this was right before she tried to tell the class that economic laws are only valid if a society believes in them - which doesn't explain why minimum wage laws still cause unemployment in the U.S.).

In any event, on the subject of greed, I might suggest "Scrooge Defended".

David, I appreciate the feedback. If we don't resort to the dictionary, what definition do we use? I'm afraid that would lead us to engage in desconstructivism ala Descartes to redefine things into the language we want, which essentially makes language meaningless. Even Descartes started realizing that towards the end of his life.

I don't think we are in that big of a disagreement with each other. I'd define the difference between self-interest and greed as follows:

Self-interest in the desire to improve our own welfare.

Greed is the desire to improve our own welfare regardless of the impact it has on others.

In your terminology, are you saying my definitiion of "self-interest" equates to your definition of "greed" and my definition of "greed" equates to your definition of "immoral greed"?

I think greed gets a bad rap because most people preceived to be primarily motivated by greed are terrible friends, neighbors, bosses, etc. There is something broken about their capacity to love, sympathize, care, and relate to others. These are not the types of people I trust nor like to spend time with.

Historically, people have always taken by force what they wanted from those weaker than themselves. What has allowed Western societies and those that emulate us to flourish is the regard for law and property rights and the use of collective force (aka the government) to protect the rights of all. In a sense, you could say that our laws restrain the negative effects of greed and channel the actions of people pursuing their own self-interest into productive and benefical effects. This is Adam Smith's "Invisible Hand" at its best.

However, this would not function without the virtue of Justice working in the background. I would argue that our Western concepts of Justice also emerged from a Christian heritage relying on Faith, Hope and Love (see Tyler Cowen's thoughts on this under the first comment on this post). Our American heritage was won through the Courage and sacrifices of many brave men and women.

I would still stick with my definition of greed, however, that it is the desire to beneift ones own interests with total disregard for the interests of others. Greed is a reality and we need institutions to restrain its harmful effects and channel the positive effects of self-interest. The more successful we are at this, the more the societal effects of greed resemble those of self-interest. That is a good thing accomplished by Justice and not by Greed.

I still don't see Greed as a positive virtue to be encouraged. Self-interest, yes. Greed, no.

I like your definition of greed Brian but I'm surprised you can't find an ethical dimension to it.

Let's look at it again. Greed is the desire to improve our own welfare regardless of the impact it has on others.

Now consider Joe the Plumber, who owns his own business. Let us suppose that Joe is like most people, in that he has little understanding of opportunity costs, creative destruction, K-H efficency and the other tools we economists take for granted when analyzing if a change is the world increases, decreases or leaves unchanged the social totals.

One day Joe discovers a radical new method of installing pipes, increasing their reliability by tenfold. Everyone wants Joe to install or improve their plumbing because they won't break down nearly as much and be able to save a lot of money. Engaging in this advancement, however, drives countless other plumbers out of buisness.

Now let's suppose Joe is greedy, by your definition. He doesn't care that he's helping some people and hurting others. He just cares that he's becoming rich, so he proceeds. The invention spreads, the plumbers (after some frictional unemployment period) get new jobs, and the world becomes wealthier.

Now let's suppose that Joe is not greedy. He invents his invention and while he's happy some people are slightly better off, he can't help but notice so many other plumbers have their lives turned upside down. Because Joe doesn't know that this is better for society as a whole in the long run, he focuses on the seen, negative effects. Guilt overcomes him and he stops selling the service, burning his notes on the amazing new technology.

In short, greeds allows people to act as if they know economics. It generates the incentive to produce a wealthier world, even if there are temporary negative side-effects.

thought says:

"However, I would propose that instead of being fixated on 'greed' let's focus on the tremendous benefits given to all of us from those who act selflessly. When one considers that our world is literally built on the massive sacrifices of others, it is humbling. I would venture that more has been contributed to society through more altruistic motivations than through 'greed.'"

Frankly, I think that's a hard assertion to back up. Look at history - more has been provided by your Carnegies, Rockafellers, and Fords than Mother Theresas. And that's not knocking Mother Theresa; she certainly deserves the respect she garnered.

But to me, it seems pretty self-evident that humans owe their material condition to entrepeneurs.

Ayn Rand is especially good at explaining this point, but unfortunately I can't think of the article(s)/essay(s) in which she writes about it.

Thought: I strong encourage you to be careful. If Joe the Plumber "killed" the technology (maybe he burned his rival's notes) he most certainly is acting out of greed but not the flavor I (or my fellow greed-loving economists) am referring to. Remember greed can be ethical or unethical. Its moral side cannot manifest if property rights are not recognized. (Again, Justice.)

Nor do I consider my example "lucky" in that it demonstrates how greed can be good. It really captures the normal process of competition and innovation. In the short run, competition is zero-sum. It's simply a matter of accounting and the only way one can be better is if another suffers. We are awash with examples.

-Dunkin' Donuts is currently revamping its franchises in order to claim a greater market share over Starbucks.

-Wal-Mart is attempting to internalize its banking so it doesn't have to use an external bank.

-Carphone Warehouse PLC started bundling free Internet with fixed-line voice calls.

-Adidas will be offering more high performance shoes in order to promote its Reebox brand.

Every one of these items, which were grabbed off of Google News today (with the exception of the first item which I heard on CNBC last night), exhibit CEOs and VPs trying to increase their wealth through competition. They know their acts will really hurt other companies--they count on it--and they certainly don't care that it will help lots of people a little bit. Otherwise they would sell it at cost. They care first and foremost that their profits will increase, just like Joe. What they may not understand (and probably don't care about) is that society as a whole will be better in the long run as a result of these improvements.

Maybe CEOs understand the wider implications of their company's level efficency and maybe they don't. I've venture it depends on the size of the company...larger ones are more likely to have to defend their "selfish" practices to the public and therefore have an incentive to know some economic theory.

Of course greed can be defined in an ethical or unethical fashion however I prefer to think of it as flavors of greed--the moral flavor being the one economists focus on when they dicuss how it is good for the economy--while general definitions are amoral...greed is fundamentally about motivation, not ethics.

And personal motivation is truly everywhere. Showing you care about people and not profit is great for a firm's image and thus probably balance sheet in the long run (like all investments, there is risk). Caring for others generates satisfaction within the caregiver and that's self interest. Having happy employees is one of the most reliable and effective ways to increase production. Etc etc.

I realize it might seem that I'm defining "greed" beyond any useful context but I implore the reader to remember two things.

1) When we talk about expanding economics (this is what my original post was about, anyway) beyond the typical ideas of money and goods and services, we must expand our defintions to something more encompassing. The economics of religion becomes useless if people can only derive satisfaction from buying things and not from the act of going to services.

2) We can even illustrate how "selfless" acts are motivated by greed even using the tighter definition offer by Thought. I can donate food in my pantry to person X and feel good about it, not caring that it will crowd out the livlihood of person Y, who sells food (assuming I buy all my food from his competitor, which is out in the suburbs where person X wouldn't ever buy from). We can use this idea to explain the motivation of many government agencies (though note this is not a moral manifestation of greed; the money and food being doled out to some people was stolen from others).

It's true that it reallys boils down to sementics. My original interest in the subject spawned from me noticing that what people meant by "greed" had entered a state of ambiguity. (See Greed: A Definition.) I'm not really sure what definition most people think of when they hear "greed" but I bet it's determined by however the speaker framed it. Considering the wide number of definitions greed can have, this suggests it's lost a solid meaning. Even the dictionary definitions are unsatisfying.

First, I need to make a correction. I put "Descartes" in my last comment and it should have been "Derrida". Sorry for the mistake.

David, you seem to be confusing "ethical" and "beneficial". Just because there can be beneficial externalities from certain forms of greed in action, that does not make it virtuous or ethical. It’s the question of ends and means. Virtue and ethics all are based on doing the right thing (means). By any common definition, greed is a wrong thing.

I'm a bit perplexed by the insistence on the word greed when self-interest is all that is needed for the market to operate. By your own words there is "ethical greed" and "unethical greed". By saying this, you are appealing to another standard that is outside of the concept of greed to evaluate it. McCloseky's and my point is that greed is neither sufficient nor necessary for a market to operate. (Let me anticipate your objection and say that I do agree that self-interest is necessary.)

You are correct that beneficial outcomes can emerge from greedy people pursuing their own ends, but that is only because they operate in an environment with other actors that are motivated by more than greed. I would even go so far as to say that I doubt a market economy would ever emerge in an environment in which greed was the highest virtue. If this was not tempered by the other virtues of Justice, Love and Hope, it would become destructive. Principles of democracy, freedom, property rights, equality, etc. all emerge from a view of people having intrinsic value. As Thought mentioned, these values have been fought for by principled men who believed in self-sacrifice for high ideals, many surrendering their lives in order to achieve it. How can greed motivate such behavior?

Greed can certainly operate on the margin in our economy and because of our systems of justice and restraint of the power of others over our lives, the negative effects of greed are constrained, while the positive effects are allowed to be played out. This is in no part due to greed, however, and instead is because institutions have been developed to constrain the harm greed can do.

David, you say greed has lost its meaning. I would say that it has not lost its meaning and that the problem is that many economists misuse the word. Self-interest is completely satisfactory to explain any of the positive effects you accredit to greed. Philosophers, theologians and societies have had negative impressions of greed for centuries. Common experience underscores this. Who ever hopes for their child to grow up to become the greediest person in the world?

I will say that self-interest and justice combine wonderfully to bring about all sorts of beneficial effects when they are played out in the marketplace. The pursuit of self-interest works to bring about these great outcomes regardless of the intention of the economic actors. However, that is not the same thing as saying that intentions do not matter. Without underlying virtues pervasive throughout a society, trust collapses and social capital is destroyed. If everyone were to operate solely from greed, society would collapse into moral decay. James Buchannan already believes the process is in motion and needs to be returned. Both he and Hayek have noted that an underlying morality is essential for a market to operate.

There is no argument that impersonal exchange often brings about beneficial outcomes that no amount of altruism by itself could ever produce. However, I believe that altruism combined with market-operations is more powerful than the market functioning without people pursuing higher purposes. The more pervasive virtuous ideals are throughout society, the more the market will generate virtuous outcomes, goods and services. Jim Collins, in his book “Good to Great”, has documented that companies and firms perform better when they are pursuing higher ideals that inspire their employees.

To dismiss companies as not caring that their products and services will benefit others is to smear the character of the people running and working in those firms for no reason. It is also an untrue view of reality. Companies would not just sell things at cost, because then they could not grow their business and make it more effective at producing positive things. If they care about their purposes at all, they would want to keep their businesses operational and profitable to maximize the good they can do. Don’t misunderstand me to say that all corporations all motivated by altruistic motives, but I am saying that you cannot say that none of them are.

Also, just because an action can be shown to have positive benefits for an individual does not mean that the individual is doing those actions merely for those positive benefits. To think of people in this manner reduces them to self-serving, constantly calculating, myopic utility maximizing automata. At that point, we might as well be Cylons (robots).

I believe the economics profession and the advancement of liberty and free-markets suffers much harm when greed is given as a rationale for their operation. The word distorts the thinking of economists and philosophers towards disdainful thinking, is publicly unpalatable (for good reason), is inaccurate, unnecessary, encourages a narrow and cynical view of humanity, fails to explain many parts of what we observe about human behavior, is inferior to the concept of self-interest, and discredits our profession in the eyes of many.

Brian,

I'm not sure if I'm confusing beneficial and ethical at all. All actions that netly benefit society are ethical actions as long as they don't violate some other ethical standard in the process (thus stealing from the rich and giving to the poor is not ethical even if total utility increases). If we look at the history of philosophy, (especially political philosophy), the central question is how to make a just society, one where as many people as possibly are as happy as possible. Naturally there is some craziness and disconnect because the strongest determinant of happiness is the success of your fellows and not the progress of society as a whole, but I find ethics and economic growth to be closely connected just the same.

I am also confused as to why you think the popular defintion of greed is satisfactory. It's arbitary; "excessive" is a matter of perspective. "Too much" is relative. My desire to redefine greed is not out of some motivation to thumb my nose out at society for the sake of doing so but to clarify what it means in light of popular opinion. (Note in last year's L3 post on the subject one definition was "demanding beyond what's earned," in which case greed would always be bad...I do not focus on that definition because that's not the one anyone else uses.)

You can always point to some firm that does not care only about greed (I am unsure how you would prove this, but I'm sure they exist) but that doesn't mean agents in the whole of capitialism need to be chiefly motivated by elements outside of greed. In fact the main complaint of capitialism is that firms only care about their bottom line. I would argue that few even care about justice; they act as if they do, however, because they are punished for unjust acts (either legally or through retribution of victimized agents). In other words, I never said other virtues were not present in capitalism, only that greed can easily be embodied by them.

While you may think my view of the greedy individual (I don't recall claiming individuals are only greedy, either, but its been a long discussion so I might have) is unrealistic and cynical, I find it to be quite the opposite. Over and over we see people wanting "too much" and over and over we see society becoming better because of it (again, given the proper institutions). Greed creates passion, drive, focus, creativity, and sometimes even an incentive for justice. Hardly the characteristics of cylons (though cylons are pretty human in the show, but whatever).

To clarify: any time a company considers it's customers' wishes, it is only doing so because that's what they are paid to do. They don't do it out of some moral obligation (generally speaking). They are doing it for greed. They act as if they care and the result is better or as good as if they really did care independent of being paid. And the result is what I would say really matters.

Post a Comment